To many people, any road race from 10km and longer is simply referred to as a “marathon.” The term has become so embedded in everyday language that it now describes any lengthy activity. This association stems from the tale of a runner in Ancient Greece who reportedly ran from Marathon to Athens, collapsing upon arrival. But how accurate is this story?

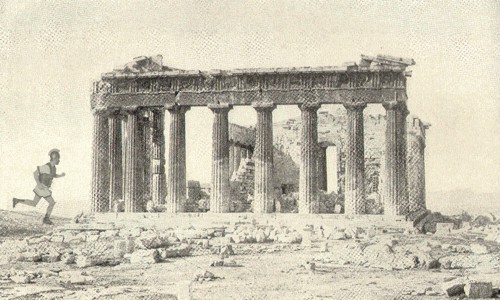

The popular legend tells of a runner named Pheidippides, who traveled from Athens to Sparta to request aid against the invading Persian forces in 490 BC. The Persian king aimed to dominate the Greek city-states that were resisting his authority. The Spartans, however, declined to assist the Athenians due to religious observances. Pheidippides returned to Athens and joined the Athenian army, which ultimately triumphed at the Battle of Marathon. He was then sent back to Athens with the message of victory, and upon arrival, he could only utter the words “Rejoice, we conquer,” before collapsing and dying. This story inspired Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, to introduce a race from Marathon to Athens in the inaugural Olympics in 1896.

However, what is the factual basis for this tale? Was there indeed a Pheidippides?

It seems there was a historical figure, although his name was likely not Pheidippides but Philippides, meaning “the son of a lover of horses” in ancient Greek. Later writers may have altered the name to fit the image of a national hero.

Herodotus, the great Greek historian, provides some insights about the runner. He notes that before departing for the Battle of Marathon, the Athenian generals summoned “a herald, Philippides, an Athenian, a hemerodromes and an expert at it… After being dispatched by the generals, this Philippides reached Sparta on the second day out from Athens.”

Philippides was thus classified as a hemerodromes, or day runner, tasked with delivering messages over Greece’s rugged terrain.

These runners were typically young men, just entering adulthood, armed only with a bow and arrow, spear, and sling for protection against wolves, bears, and robbers in the mountains. It appears Philippides may have been older than most hemerodroi, given his expertise.

He reportedly arrived in Sparta within 48 hours, with various ancient sources suggesting that the distance between the two cities was around 1,200 stades (approximately 136.3 miles or 219.3 km). A run from Athens to Sparta by a group of Royal Air Force runners led John Foden and Colonel N. Hammond, a former Cambridge history professor, to study the possible routes taken by Philippides. Their findings inspired the modern Spartathlon race, which began in 1983.

Foden and Hammond considered the accounts of contemporaries like Herodotus and the political dynamics among the city-states, several of which allied with the Persians. They proposed that Philippides left Athens at dawn, traveling along the Sacred Way to Eleusis, then following the Coastal Scironian Way from Megara to Corinth. His path likely continued through fertile areas and along the river through the Zapartis Valley. Eventually, he would face rocky terrain leading to the Pathenian mountain range.

The specifics of his route remain uncertain. He might have crossed hostile land, which would involve navigating six foothills and five rivers, or he may have chosen a flatter but still undulating route before reaching Sparta. This journey is estimated to cover around 155 miles (250 km) based on modern measurements. Philippides is believed to have completed the run in under 48 hours, likely finishing in 41-42 hours, a feat achievable for a seasoned long-distance runner. In fact, all 15 finishers of the first Spartathlon, who were unfamiliar with the course, completed it in less than 36 hours.

While Philippides’ run from Athens to Sparta appears to be historically documented, the dramatic account of his final run from Marathon to Athens and his death is less reliable. Modern Greek scholars have determined this aspect was likely added later.

Herodotus, who lived from 484 to 425 BC and could have consulted veterans of the Battle of Marathon, does not mention Philippides or anyone else running from Marathon to Athens. It wasn’t until 500 years later that this second run was incorporated into the story, with one writer attributing it to Philippides while others mentioned a Eucles and a Thersippus.

It was not uncommon for long-distance runners to collapse after extreme exertion, as shown by the deaths of British runners Woolley Morris and Gryffydd Morgan in the 18th century. However, the notion of a runner dying after reaching their goal seems to have been a narrative embellishment common in later Greek literature during the Roman period. Besides the well-known Marathon to Athens episode, another story tells of a runner named Euchidas, who collapsed after a round trip from Platea to Delphi.

Therefore, it seems that the story of the run from Marathon to Athens is likely a later invention, crafted to add drama to an already remarkable long-distance run. The first official run from Marathon to Athens probably took place not in 490 BC but rather in 1896 AD.

This article was written by Andy Milroy. Sources include The Hemerodromoi by Victor J. Matthews, The Marathon Footrace by Roger Gynn and David Martin, The Long Distance Record Book by Andy Milroy, and The Pheidippides Route by Mike Callaghan.