Running for an hour holds a unique fascination for distance runners, balancing the intensity of a short sprint with the endurance required for long-distance running. Unlike the grueling demands of ultra-endurance challenges, a 60-minute run offers a sweet spot—demanding enough to test an athlete’s physical and mental resilience but not so extreme that it becomes an ordeal. This balance is what has made the Hour run an enduring and respected athletic event since its inception. The simplicity of seeing how far one can go within a set time, rather than aiming for a fixed distance, offers a universal appeal and has attracted runners for centuries. The history of the Hour race stretches back through time, and although much of its early history is shrouded in mystery, the stories we know provide a fascinating glimpse into the evolution of distance running as a sport.

The Origins of the Hour Run: Betting, Legends, and Disasters

The earliest recorded Hour runner was Edward or Edmund Preston, a butcher from Leeds who lived during the late 17th century. Known for regularly competing over distances of 10 to 12 miles, Preston was a formidable athlete for his time, easily running 10 miles in under an hour. In those days, running events were often tied to gambling, with entire fortunes wagered on the outcome of a single race. Spectators were not merely observers but active participants, betting on their chosen athletes with a fervor that sometimes led to financial ruin.

Preston’s most famous race took place when he competed against the King’s footman in front of a crowd of thousands, many of whom bet everything they had. Preston won the race, and the fallout was severe—families who had staked their horses on the outcome were left to walk home, penniless. This story highlights the high stakes of running during this period, where the risk of financial ruin was as real as the physical toll on the athletes themselves.

Following his victory, Preston became something of a marked man, and his career took a dramatic turn. A nobleman sent him to London under an assumed identity, and he raced under the guise of a miller. In an attempt to hide his true identity, the nobleman even arranged for Preston to be disfigured. Despite these extreme measures, Preston continued to excel, winning races and earning large sums of money for his patrons. These early stories of betting and deception set the tone for a sport that was both thrilling and dangerous.

However, the risks extended beyond financial loss. In the mid-18th century, distance running took a tragic turn with several athletes dying as a result of pushing their bodies too far. Woolley Morris set a new world best by running 10 miles in 54:30, but he collapsed and died shortly after. Similarly, Guto Nythbran, a famous Welsh runner, completed a 10.4-mile race from Newport to Bedwas in under an hour, only to die from an overenthusiastic slap on the back by a fan. These incidents highlighted the physical risks of the sport, and for a time, British runners became more cautious, avoiding the extreme performances that had claimed the lives of Morris and Nythbran.

The Hour Run Crosses the Atlantic: The Rise of Organized Competitions

By the mid-19th century, the Hour run began to evolve into a more formalized competition, particularly in the United States. In 1844, a $1,000 prize was offered to the runner who could cover the greatest distance within an hour. The race was held at the Beacon course in Hoboken, New Jersey, a mile-long loop, and drew an enormous crowd. Over 30,000 spectators turned up, and many broke down the fences to get in without paying. Betting was rampant, and the race attracted not only American runners but also several from Britain, including Native American competitors.

John Gildersleeve, an American, ultimately won the race, covering a distance of 10 miles and 955 yards in 60 minutes. This event’s success inspired further organized races, and British runners frequently crossed the Atlantic to compete against their American counterparts. William Howitt, racing under the name William Jackson for family reasons, was one of the most successful British competitors during this time. The Hour race, with its simple premise, proved a popular format, and it continued to grow in prominence throughout the 19th century.

Back in England, distance running gained even more attention with matches that often took on the air of national championships. One of the most famous races took place between Howitt and his archrival William Sheppard on the Hatfield Turnpike, a hilly, two-mile stretch of road between two milestones. This race was designed to settle who could claim to be the champion runner of England, and it drew crowds from all over the country. After a fast start, with the two men running the first mile in just over five minutes, Sheppard led at the 10-mile mark with a time of 53:35. However, he collapsed soon after, and Howitt went on to become the first man to run over 11 miles within the hour.

The success of races like these spurred the development of running tracks in major industrial cities, often funded by the owners of local public houses. These tracks were rudimentary by today’s standards—irregular in shape and size, with trees sometimes obstructing the view—but they allowed for more organized competition. The sport was growing, and with it came a new generation of runners, eager to push the limits of human endurance.

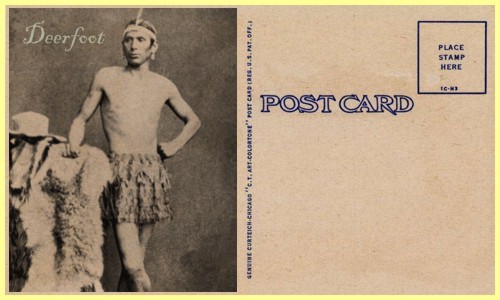

Enter the Professionals: The American Sensation Deerfoot

One of the most exciting developments in distance running came in 1861 with the arrival of Louis Bennett, better known as Deerfoot. A member of the Eagle tribe of the Seneca nation, Deerfoot’s appearance in Britain caused a sensation. He ran in traditional Native American attire—a beech-clout and moccasins—and his unique running style, which included sudden bursts of speed, disrupted the pacing strategies of his English competitors. Though he lost his first race, having just completed a long trans-Atlantic journey, Deerfoot quickly found his form and became one of the most popular attractions in British distance running.

Despite his success, Deerfoot’s attire, particularly his bare chest and short beech-clout, was considered too revealing for some spectators, especially women. As a result, he was eventually required to run in a more modest outfit consisting of a guernsey and long drawers. Nevertheless, his performances were extraordinary, and in one race, he covered 11 miles and 970 yards within an hour—a feat that remained the world record for several decades. Deerfoot’s influence on the sport was profound, drawing large crowds and helping to popularize distance running in Britain.

Amateurs and the Rise of Record-Breaking Performances

By the late 19th century, distance running began to attract a new breed of amateur runners who sought to emulate the feats of professionals like Deerfoot. Among these amateurs was Walter George, considered one of the greatest distance runners of his time. Though George never officially broke Deerfoot’s Hour record in competition, he claimed to have surpassed it during time trials, recording a time of 59:29 for 12 miles. George’s achievements helped elevate the status of amateur distance running, and his performances inspired future generations of athletes.

The early 20th century saw further advances in the Hour run, with athletes like Alf Shrubb setting new records. Shrubb, a dominant force in British distance running, recorded an impressive 11 miles and 1137 yards within an hour in 1904. His success was not limited to the Hour run; Shrubb excelled across a range of distances, building up huge leads in races before slowing down to allow his opponents to catch up, only to surge ahead once again. This playful style of racing endeared him to spectators and cemented his reputation as one of the sport’s all-time greats.

The first Olympic medalist to hold the Hour record was Jean Bouin of France, who lost by a narrow margin to Hannes Kolehmainen in the 1912 Olympic 5,000 meters. Bouin, who had narrowly missed breaking the Hour record in 1911, finally succeeded in 1913, covering a distance of 11 miles and 1442 yards. Tragically, Bouin’s career was cut short when he died during World War I, but his achievements left a lasting legacy in the world of distance running.

The Era of the Flying Finns and Beyond

In the 1920s and 1930s, distance running was dominated by Finnish athletes, particularly Paavo Nurmi. Widely regarded as one of the greatest runners of all time, Nurmi won nine Olympic gold medals and set numerous world records at various distances. In 1928, he turned his attention to the Hour run, adding 200 yards to Bouin’s record. The tradition of 10,000-meter record holders attempting to break the Hour run continued throughout the 20th century, with athletes like Viljo Heino of Finland and Emil Zatopek of Czechoslovakia both setting new records. Zatopek’s 1951 performance, in which he became the first man to run 20 kilometers in an hour, remains one of the most impressive achievements in the history of the sport.

As the sport progressed, records continued to fall. Ron Clarke of Australia broke the Hour record in 1965, becoming only the second man in history to hold world records for 3 miles, 5,000 meters, 6 miles, 10,000 meters, 10 miles, and 20,000 meters. Clarke’s feat was matched by Gaston Roelants of Belgium, who broke the Hour record twice in the 1970s. Roelants, a former steeplechase champion, added over 120 meters to Clarke’s record in 1972, further cementing his place in distance running history.

The Women’s Hour Event and Modern Competitions

Women’s Hour races began in the early 20th century but did not gain widespread recognition until the 1970s. Toshiko Seko set the first widely recognized record, and since then, athletes like Ingrid Kristiansen, Tegla Loroupe, and Dire Tune have pushed the boundaries of women’s distance running. Kristiansen held the record for over a decade, and in 2008, Tune became the first woman to surpass the 18,000-meter mark, setting a new benchmark for future competitors.

While the Hour run may not receive the same level of attention as marathons or other high-profile distance races, it remains a test of endurance, strategy, and pacing. The sport continues to evolve, with new athletes pushing the limits of human performance. Whether in the early days of gambling and deception or the modern era of professional competition, the Hour run has always captured the spirit of distance running at its finest.